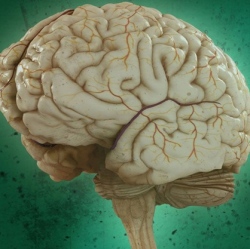

Psychosis’ devastating toll on memory arises from dysfunction of frontal and temporal lobes in the brain that rob sufferers of the ability to make associative connections, a study has found, pinpointing potential target areas for new treatments for thoes for whom medication does not help the struggle to remember.

The study found that memory is most impaired when people with schizophrenia try to form relationships between items, remembering to also buy eggs, milk and butter when buying flour to make pancakes, and that this relational encoding problem is accompanied by regionally specific dysfunction in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

People with schizophrenia also have greater difficulty retrieving this relational information even when they can remember the individual items, and this relational retrieval deficit is accompanied by functionally specific dysfunction in a brain area called the hippocampus. The research is published online today in JAMA Psychiatry.

Schizophrenia is well-known for its more florid manifestations, said J. Daniel Ragland, professor of psychiatry in the UC Davis School of Medicine and lead author of the study.

“Everyone has had the experience of hearing their name called or phone ring, or that someone is standing beside them. When these events take place initially we experience them as real,” Ragland said. “What happens in psychosis is that you continue to have the experience, and the feeling becomes more developed, more real and more intrusive.”

Decades-old medications treat these symptoms effectively. But what remains is often more intractable: memory loss and other cognitive difficulties that make it difficult to perform the activities of daily living.

“People with schizophrenia have difficulty retrieving associations within a context, and this creates a pervasive loss of memory that makes everyday life a challenge,” Ragland said. “You can’t work if you can’t remember the next step in what your boss told you to do.”

“If you’re going to develop a drug or other therapy to improve memory, we found that this frontal and temporal lobe relational memory network may be a target or ‘biomarker’ for treatment development,” he said.