Their "semantic atlas" shows how, for example, one region of the brain activates in response to words about clothing and appearance. The researchers found that these maps were quite similar across the small number of individuals in the study, even down to minor details. The work, by a team at Berkeley, is published in the journal Nature.

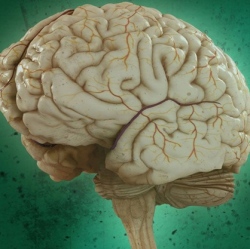

It had previously been proposed that information about words’ meaning was represented in a group of brain regions known as the semantic system. But the new work uncovers the fine detail of this network, which is spread right across the outer layer of the human brain.

The team collected data on changes in blood flow and oxygenation – indicators of activity – in different areas of the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is the brain’s outer layer of tissue, playing a key role in higher functions such as language and consciousness.

The brain imaging data were matched against time-coded transcriptions of the stories. The researchers then used a computer algorithm that scored words according to how closely they are related in terms of meaning.

The results were converted into a thesaurus-like map where the words were arranged on the left and right hemispheres of the brain. They show that the semantic system is distributed broadly in more than 100 distinct areas across both halves – hemispheres – of the cortex and in intricate patterns that were consistent across individuals in the study.

The maps show that many areas of the human brain represent language describing people and social relations rather than abstract concepts. But the same word could be repeated several times on different parts of the brain map. For example, the word "top" was represented in a part of the brain that responds to words about clothing and appearance, and also in a region that deals with numbers and measurements.

"Our semantic models are good at predicting responses to language in several big swaths of cortex," said Dr Huth. "But we also get the fine-grained information that tells us what kind of information is represented in each brain area. That’s why these maps are so exciting and hold so much potential."

Scientists could track the brain activity of patients who have difficulty communicating and then match that data to language maps to determine what their patients are trying to express. "Although the maps are broadly consistent across individuals, there are also substantial individual differences," said the study’s senior author Jack Gallant.

"We will need to conduct further studies across a larger, more diverse sample of people before we will be able to map these individual differences in detail."