3 participants with movement impairment controlled an onscreen cursor by imagining their own hand movements. The report involved three study participants with severe limb weakness, two from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and one from a spinal cord injury.

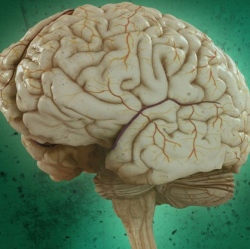

They each had one or two baby-aspirin-sized electrode arrays placed in their brains to record signals from the motor cortex, a region controlling muscle movement. These signals were transmitted to a computer via a cable and translated by algorithms into point-and-click commands guiding a cursor to characters on an onscreen keyboard.

Each participant, after minimal training, mastered the technique sufficiently to outperform the results of any previous test of brain-computer interfaces, or BCIs, for enhancing communication by people with similarly impaired movement. Notably, the study participants achieved these typing rates without the use of automatic word-completion assistance common in electronic keyboarding applications nowadays, which likely would have boosted their performance.

One participant, Dennis Degray of Menlo Park, California, was able to type 39 correct characters per minute, equivalent to about eight words per minute.

The investigational system used in the study, an intracortical brain-computer interface called the BrainGate Neural Interface System*, represents the newest generation of BCIs. Previous generations picked up signals first via electrical leads placed on the scalp, then by being surgically positioned at the brain’s surface beneath the skull.

An intracortical BCI uses a tiny silicon chip, just over one-sixth of an inch square, from which protrude 100 electrodes that penetrate the brain to about the thickness of a quarter and tap into the electrical activity of individual nerve cells in the motor cortex.

Shenoy said the day will come, closer to five than 10 years from now, he predicted, when a self-calibrating, fully implanted wireless system can be used without caregiver assistance, has no cosmetic impact and can be used around the clock.

“I don’t see any insurmountable challenges.” he said. “We know the steps we have to take to get there.”

Degray, who continues to participate actively in the research, knew how to type before his accident but was no expert at it. He described his newly revealed prowess in the language of a video game aficionado.

“This is like one of the coolest video games I’ve ever gotten to play with,” he said. “And I don’t even have to put a quarter in it.”