If technological progress, known in the chip industry as Moore’s Law, had ended a decade ago, as some people predicted, we wouldn’t have had smartphones or tablets.

The electronics world would have been very different. It would have been more primitive than it is today, and we might not have cool apps like Angry Birds, according to Bob Colwell, director of the microsystems technology officer at the government’s research think tank, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

And now, Moore’s Law may be coming to an end and chip designers should really come up with tricks that will keep technology moving forward even if they don’t get the kind of enormous free advances that they used to get in the past, Colwell said.

The end of Moore’s Law has been predicted for almost as long as it has been around.

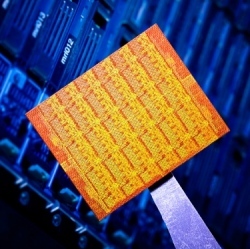

Gordon Moore, chairman emeritus of Intel, predicted in 1965 that the number of transistors –basic on-off switches that are the fundamental building blocks of modern electronics — on a chip would double every two years or so. Intel’s first microprocessor, the 4004, had just 2,300 transistors on a chip when it was introduced in 1971. Now, Nvidia’s Kepler-based Titan graphics chips have more than 7 billion transistors on a single chip. That’s what 42 years of chip doublings have gotten us.

But Colwell, who made his remarks at the Hot Chips engineering conference at Stanford University in a keynote speech on Monday, believes that it’s time to think about an end. The laws of physics are preventing further gains through simple miniaturization — which has made chips smaller, faster, and less power hungry over the years. Now problems such as power consumption and atomic variation are creating barriers.

Silicon Valley has long wagered that Moore’s Law will keep going. But Colwell believes that the time will come to figure out what will happen if Moore’s Law comes to an end. He knows what he is talking about since Colwell was a longtime chip architect at Intel, heading projects such as the extremely successful Pentium II processor. In 1997, he was named an Intel Fellow, the highest technical rank at the company.