Researchers who transplanted human brain cells into newborn mice said the rodents grew up to be smarter than their normal littermates, learning how to associate a tone with an electric shock more quickly and finding escape hatches faster.

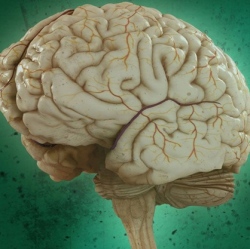

The experiments are aimed at making models to study human brain diseases such as Huntington’s and schizophrenia, as well as nerve diseases such as multiple sclerosis. But the team at the University of Rochester say their findings also suggest that these brain cells, called glial cells, may very well be one of the important factors that make humans different from other animals.

“Human cognitive evolution might be the product of glial evolution,” said Dr. Steven Goldman, who worked with his partner and wife Dr. Maiken Nedergaard on the study. Their findings also support the growing theory that glia cells, one of the important components of the brain’s so-called white matter, are far from being passive support cells and are in fact actively involved in brain function.

Down the road, Goldman hopes the findings might lead to procedures to transplant brain cells to treat diseases as diverse as multiple sclerosis, bipolar disease and even the brain shrinkage that causes memory loss in aging.