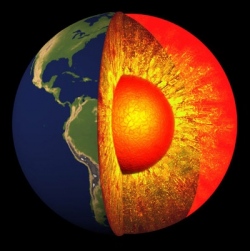

Under extreme pressures and temperatures, one of the main metals of the Earth’s interior has exhibited a never-before-seen transition.

Iron oxide was subjected to conditions similar to those at the depth where the Earth’s innermost two layers meet.

At 1,650C and 690,000 times sea-level pressure, the metal changed the degree to which it conducted electricity.

But, as the team outlined in Physical Review Letters, the metal’s structure was surprisingly unchanged.

The finding could have implications for our as-yet incomplete understanding of how the Earth’s interior gives rise to the planet’s magnetic field.

While many transitions are known in materials as they undergo nature’s extraordinary pressures and temperatures, such changes in fundamental properties are most often accompanied by a change in structure.

These can be the ways that atoms are arranged in a crystal pattern, or even in the arrangement of subatomic particles that surround atomic nuclei.