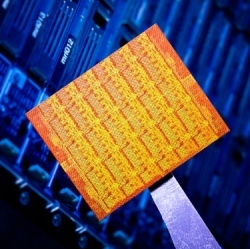

Transparent electronics (pioneered at Oregon State University) may find one of their newest applications as a next-generation replacement for some uses of non-volatile flash memory, a multi-billion dollar technology nearing its limit of small size and information storage capacity.

Researchers at OSU have confirmed that zinc tin oxide, an inexpensive and environmentally benign compound, could provide a new, transparent technology where computer memory is based on resistance, instead of an electron charge.

This resistive random access memory, or RRAM, is referred to by some researchers as a “memristor.” Products using this approach could become even smaller, faster and cheaper than the silicon transistors that have revolutionized modern electronics — and transparent as well.

Transparent electronics offer potential for innovative products that don’t yet exist, like information displayed on an automobile windshield, or surfing the web on the glass top of a coffee table.

“Flash memory has taken us a long way with its very small size and low price,” said John Conley, a professor in the OSU School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. “But it’s nearing the end of its potential, and memristors are a leading candidate to continue performance improvements.”

Memristors: faster than flash

Memristors have a simple structure, are able to program and erase information rapidly, and consume little power. They accomplish a function similar to transistor-based flash memory, but with a different approach. Whereas traditional flash memory stores information with an electrical charge, RRAM accomplishes this with electrical resistance. Like flash, it can store information as long as it’s needed.

Flash memory computer chips are ubiquitous in almost all modern electronic products, ranging from cell phones and computers to video games and flat panel televisions.