More than 100 drugs have been approved to treat cancer, but predicting which ones will help a particular patient is difficult. Now a new implantable device that can carry small doses of up to 30 different drugs promises to allow researchers to measure how effectively each one kills the cancer cells.

Such a device could eliminate much of the guesswork now involved in choosing cancer treatments, says Oliver Jonas, lead author of a paper describing the device in the April 22 issue of Science Translational Medicine. “You can use it to test a patient for a range of available drugs, and pick the one that works best,” Jonas says.

Putting the lab in the patient:

Most of the commonly used cancer drugs work by damaging DNA or otherwise interfering with cell function. Recently, scientists have also developed more targeted drugs designed instead to only kill tumor cells that carry a specific genetic mutation. However, it is usually difficult to predict whether a particular drug will be effective in an individual patient.

In some cases, doctors extract tumor cells, grow them in a lab dish, and treat them with different drugs to see which ones are most effective. However, this process removes the cells from their natural environment, which can play an important role in how a tumor responds to drug treatment, Jonas says.

“The approach that we thought would be good to try is to essentially put the lab into the patient,” he says. “It’s safe and you can do all of your sensitivity testing in the native microenvironment.”

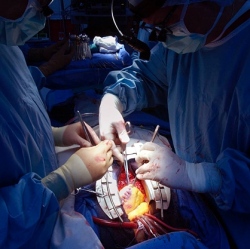

The device, made from a stiff, crystalline polymer, can be implanted in a patient’s tumor using a biopsy needle. After implantation, drugs seep 200 to 300 micrometers into the tumor, but do not overlap with each other. Any type of drug can go into the reservoir, and the researchers can formulate the drugs so that the doses that reach the cancer cells are similar to what they would receive if the drug were given by typical delivery methods such as intravenous injection.

After one day of drug exposure, the implant is removed, along with a small sample of the tumor tissue surrounding it. The researchers analyze the drug effects by slicing up the tissue sample and staining it with antibodies that can detect markers of cell death or proliferation.