A revolutionary blood cancer treatment that genetically modifies patient cells to fight the disease cuts the risk of it progressing by 74%, a world-first clinical trial has found.

The therapy, ciltacabtagene autoleucel, “significantly slows or stops progression” of multiple myeloma in patients who have stopped responding to other treatments, according to the study.

The results were presented in Chicago at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s (Asco) annual meeting, the world’s largest cancer conference.

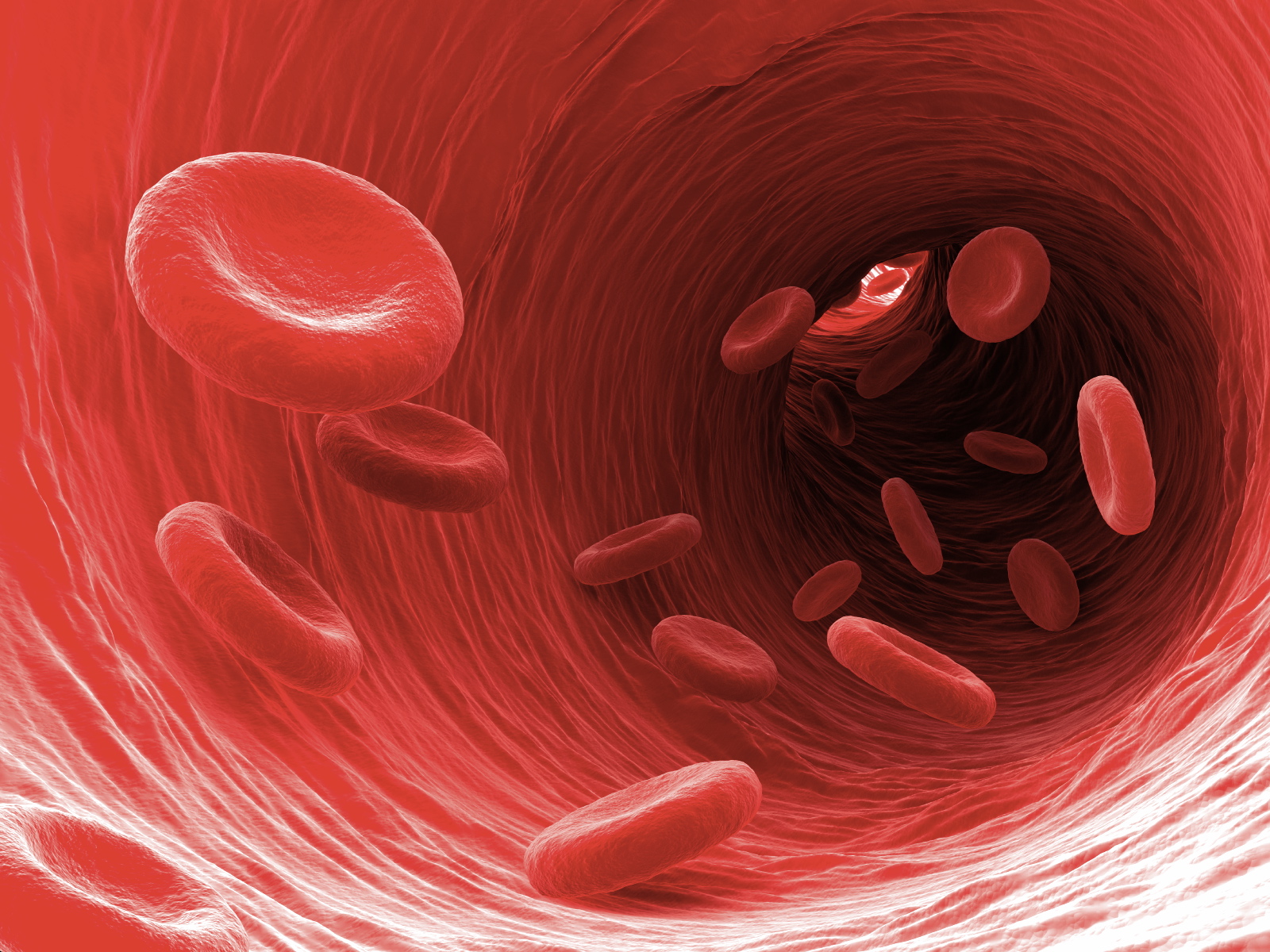

Multiple myeloma is an incurable blood cancer that affects a type of white blood cell called plasma cells, found in the bone marrow. An estimated 176,404 people around the world were diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2020, according to Asco.

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, also known as Carvykti, belongs to a class of drugs known as Car-T therapies. They work by weaponising a patient’s own disease-fighting T-cells, genetically engineering them to target specific proteins on cancer cells, and replacing them to seek out and attack cancer.

The Cartitude-4 study is the first and only clinical trial of its kind in the world. The global late-stage trial included 419 people with multiple myeloma who had already had one to three forms of treatment, including lenalidomide, which was no longer effective. Lenalidomide is the most common treatment for multiple myeloma.

“Lenalidomide has become a foundation of care for people with myeloma, but as its use has expanded, so has the number of patients whose disease will no longer respond to the treatment,” said Dr Oreofe Odejide, an Asco expert who was not involved in the study.

“Ciltacabtagene autoleucel has not only shown that it delivers remarkably effective outcomes compared to patients’ current options, but also that it can be used safely earlier in the treatment phase.”

The trial enrolled participants from 16 countries, including the US and Australia.

The groundbreaking treatment works by removing some T-cells from a patient’s blood, which are then modified in a laboratory, so they have specific proteins called receptors. The receptors allow the modified T-cells to recognise the cancer cells.

When the modified T-cells are returned to the patient’s body, they seek out and destroy cancer cells.

After an average follow-up of 16 months, the researchers found that ciltacabtagene autoleucel reduced the risk of cancer spreading or growing by 74%, compared with standard treatments.

“Lenalidomide-based therapies are used extensively as frontline treatments, in both young and elderly patients and including those who are transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible,” said the lead study author Dr Binod Dhakal, of Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

“This causes an increase in the number of cases where the disease no longer responds to lenalidomide early in the course of the disease. These findings show that ciltacabtagene autoleucel is highly effective in patients with lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma as early as after first relapse.”

The treatment is already available to some patients in the US and parts of Europe but not yet in the UK.