Swiss researchers have succeeded in measuring changes in strong magnetic fields with unprecedented precision, they report in the open-access journal Nature Communications. The finding may find widespread use in medicine and other areas.

In their experiments, the researchers at the Institute for Biomedical Engineering, which is operated jointly by ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich, magnetized a water droplet inside a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner, a device used for medical imaging. The researchers were able to detect even the tiniest variations of the magnetic field strength within the droplet. These changes were up to 10-12 (1 trillion) times smaller than the 7 tesla field strength of the MRI scanner used in the experiment.

“Until now, it was possible only to measure such small variations in weak magnetic fields,” says Klaas Prüssmann, Professor of Bioimaging at ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich. An example of a weak magnetic field is that of the Earth, where the field strength is just a few dozen microtesla. For fields of this kind, highly sensitive measurement methods are already able to detect variations of about a trillionth of the field strength, says Prüssmann. “Now, we have a similarly sensitive method for strong fields of more than one tesla, such as those used … in medical imaging.”

The scientists based the sensing technique on the principle of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), which also serves as the basis for magnetic resonance imaging and the spectroscopic methods that biologists use to elucidate the 3D structure of molecules, but with 1000 times greater sensitivity than current NMR methods.

The scientists carried out an experiment in which they positioned their sensor in front of the chest of a volunteer test subject inside an MRI scanner. They were able to detect periodic changes in the magnetic field, which pulsated in time with the heartbeat. The measurement curve is similar to an electrocardiogram (ECG), but measures a mechanical process (the contraction of the heart) rather than electrical conduction.

“We are in the process of analyzing and refining our magnetometer measurement technique in collaboration with cardiologists and signal processing experts,” says Prüssmann. “Ultimately, we hope that our sensor will be able to provide information on heart disease, and do so non-invasively and in real time.”

The new measurement technique could also be used in the development of new contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging and improved nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for applications in biological and chemical research.

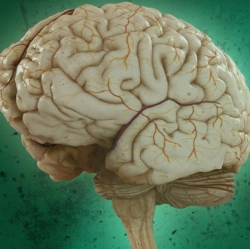

In a related development, MIT scientists hoping to get a glimpse of molecules that control brain activity have devised a new sensor that allows them to image these molecules without using any chemical or radioactive labels (which feature low resolution and can’t be easily used to watch dynamic events).

The new sensors consist of enzymes called proteases designed to detect a particular target, which causes them to dilate blood vessels in the immediate area. This produces a change in blood flow that can be imaged with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or other imaging techniques.

“This is an idea that enables us to detect molecules that are in the brain at biologically low levels, and to do that with these imaging agents or contrast agents that can ultimately be used in humans,” says Alan Jasanoff, an MIT professor of biological engineering and brain and cognitive sciences. “We can also turn them on and off, and that’s really key to trying to detect dynamic processes in the brain.”

In a paper appearing in the Dec. 2 issue of open-access Nature Communications, Jasanoff and his colleagues explain that they used proteases (sometimes used as biomarkers to diagnose diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s disease) to demonstrate the validity of their approach. But now they’re working on adapting these imaging agents to monitor neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin, which are critical to cognition and processing emotions.

“What we want to be able to do is detect levels of neurotransmitter that are 100-fold lower than what we’ve seen so far. We also want to be able to use far less of these molecular imaging agents in organisms. That’s one of the key hurdles to trying to bring this approach into people,” Jasanoff says.

“Many behaviors involve turning on genes, and you could use this kind of approach to measure where and when the genes are turned on in different parts of the brain,” Jasanoff says.

His lab is also working on ways to deliver the peptides without injecting them, which would require finding a way to get them to pass through the blood-brain barrier. This barrier separates the brain from circulating blood and prevents large molecules from entering the brain.

Jeff Bulte, a professor of radiology and radiological science at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, described the technique as “original and innovative,” while adding that its safety and long-term physiological effects will require more study.

“It’s interesting that they have designed a reporter without using any kind of metal probe or contrast agent,” says Bulte, who was not involved in the research. “An MRI reporter that works really well is the holy grail in the field of molecular and cellular imaging.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative, the MIT Simons Center for the Social Brain, and fellowships from the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds and the Friends of the McGovern Institute.