The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is operating again after its winter break.

Early on Thursday, opposing stable beams of protons were smashed into each other at four observation positions.

The total collision energy in these bunches of sub-atomic particles was eight trillion electron volts – a world record.

Scientists expect the big boost in capability to significantly increase the collider’s chances of discovering "new physics".

The great expectation is that they will definitively confirm or deny the existence of the Higgs boson, the elusive particle that would help explain why matter has mass.

"The experience of two good years of running at 3.5 TeV per beam gave us the confidence to increase the energy for this year without any significant risk to the machine," explained Steve Myers, the director for accelerators and technology at Cern (European Organization for Nuclear Research).

"Now it’s over to the experiments to make the best of the increased discovery potential we’re delivering them!"

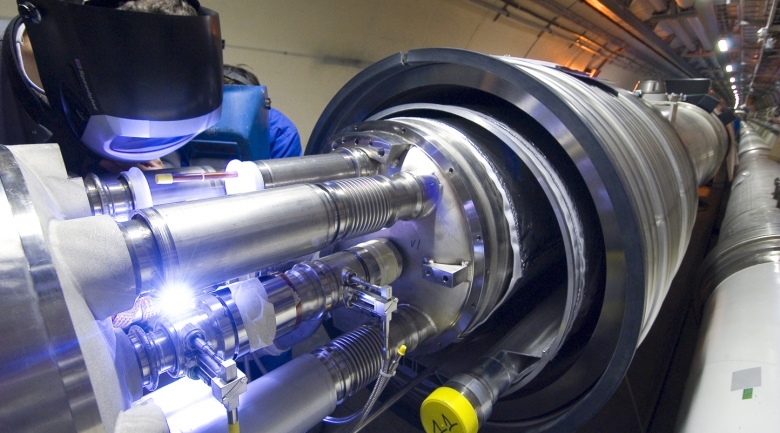

Since first switching on in 2008, operators at the LHC have cautiously increased the energy contained in each of the bunches of protons sent around the 27km collider, which lies beneath the Franco-Swiss border.

It is planned that the collider will collect data until November, after which it will be upgraded during a shutdown period that will last 20 months.

That should result in an operating proton beam energy of 14 trillion electronvolts, or teraelectronvolts – another great leap in capability.

The LHC collaboration hopes to reach that milestone in 2014, re-starting the hunt for novel physics in early 2015.

In the 2012 run of experiments, the Higgs will be a key focus.

Teams working on the two major detectors at the facility announced at the end of last year that they had seen hints of the particle, but stopped short of claiming they had seen it with certainty.

Anticipation was then further heightened a month ago by news that the recently closed Tevatron collider, based at the US national laboratory Fermilab, had also seen a "bump" in its archived data around the same mass region as that observed by the LHC detectors. That is, a particle with a mass of about 125 gigaelectronvolts (GeV; this is about 130 times as heavy as the protons found in atomic nuclei).

The new data collection phase will settle the issue, researchers believe.

Running the LHC at higher energies makes it more likely that Higgs particles, if they exist, will show themselves in the debris of the proton collisions.

"The increase in energy is all about maximising the discovery potential of the LHC," said Cern Research Director Sergio Bertolucci. "And in that respect, 2012 looks set to be a vintage year for particle physics."