The growth pattern of long-range connections in the brain predicts how a child’s reading skills will develop, according to research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Nature News reports.

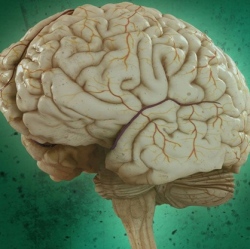

Literacy requires the integration of activity in brain areas involved in vision, hearing and language. These areas are distributed throughout the brain, so efficient communication between them is essential for proficient reading.

Jason Yeatman, a neuroscientist at Stanford University in California, and his colleagues studied how the development of reading ability relates to growth in the brain’s white-matter tracts, the bundles of nerve fibers that connect distant regions of the brain.

They tested how the reading skills of 55 children aged between 7 and 12 years old developed over a three-year period. There were big differences in reading ability between the children, and these differences persisted — the children who were weak readers relative to their peers at the beginning of the study were still weak three years later.

The growth of white-matter tracts is governed by pruning, the process that eliminates extraneous nerve fibres and neuronal connections; and myelination, in which individual nerve fibres in the tracts are enveloped by a fatty, insulating tissue that increases the speed of transmission. Both processes are influenced by experience — underused nerve fibres are pruned, whereas others are myelinated — so they occur at different rates and times in different people.

Yeatman says that individual children might benefit from reading lessons that are tailored to their patterns of brain development. In the future, it may be possible to determine exactly when pruning is taking place — children may find it easiest to learn to read at this stage of development, when there is greater potential for remodelling in the brain. “We’d really like to find a way of predicting who’s going to struggle with reading before they start struggling,” he says.