Researchers are describing that the human body is much more strange and pliable than previously thought — and that’s a good thing. A shining example is the work of Professor Deepak Srivastava, MD, a professor at the Univ. of California – San Francisco (UCSF) and its affiliate Gladstone Institute labs. Dr. Srivastava first discovered that a cocktail of three genes injected into mice could provoke fibroblast cells to become cardiomyocytes — the cells that pump blood in a beating heart. Now his team has managed to use a slightly more advanced formulation to get human fibroblasts to do the same thing.

I. Cardiofibroblasts Offer a Ready Made Stock of Cells For Heart Repair in Mice

While the holy grail of tissue engineering has long thought to have been to develop fully pluripotent, sustainable stem cell colonies and then trigger them to differentiate into desired cells of any kind, that has proven tricky in practice. Complex tissue parameters — pressure, local nutrients, and signals from surrounding cells — have all been found to influence what target a stem cell decides to become, making what seemed an easy route far harder. So some researchers like Dr. Srivastava have turned in part to look into ways to trick local cell types near a damaged tissue into becoming the type of cells in the healthy version of that tissue via gene therapy.

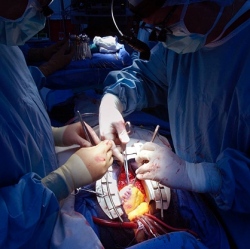

Repairing a (literally) broken heart is one attractive target: every year nearly 600,000 Americans die of heart disease. Heart disease is the number one killer in the U.S., according to the latest statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It accounts for nearly 600,000 deaths in the U.S. a year, or just under 1 in 4 deaths.