Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a way to trigger reproduction in the laboratory of clusters of human cells that make insulin, potentially removing a significant obstacle to transplanting the cells as a treatment for patients with type 1 diabetes.

Efforts to make this treatment possible have been limited by a dearth of insulin-producing beta cells that can be removed from donors after death, and by the stubborn refusal of human beta cells to proliferate in the laboratory after harvesting.

The new technique uses a cell conditioning solution originally developed to trigger reproduction of cells from the lining of the intestine.

“Until now, there didn’t seem to be a way to reliably make the limited supply of human beta cells proliferate in the laboratory and remain functional,” said Michael McDaniel, PhD, professor of pathology and immunology. “We have not only found a technique to make the cells willing to multiply, we’ve done it in a way that preserves their ability to make insulin.”

The findings are now available in PLOS ONE (open access).

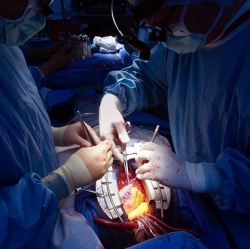

The current method for harvesting human islets, which are comprised primarily of the insulin-producing beta cells, makes it necessary to find two or three donors to extract enough cells to produce an adequate supply of insulin to treat a single patient with diabetes.

The idea for the new technique came from an on-campus gathering to share research results. Lead author Haytham Aly, PhD, a postdoctoral research scholar, reported on his work with beta cells and was approached by Thaddeus Stappenbeck, MD, PhD, associate professor of pathology and immunology, who studies autoimmune problems in the gut. Stappenbeck had developed a medium that causes cells from the intestine’s lining to proliferate in test tubes.